Sense making

When the map doesn't match the terrain

When the map doesn’t match the terrain.

This is a common experience for leaders; the day doesn’t go as planned or a situation arises that we were not expecting at all. This could be in a classroom, a whole school issue or a national crisis.

The terrain is the reality of school life while the map represents what we think we know about school life. Often there will be a difference between the map and the terrain; sometimes small and insignificant but sometimes critical to the school.

That moment when we realise that the map and terrain do not match requires leadership. It requires us to make sense of what is happening in order to make decisions. But schools are complex systems where cause and effect are impossible to untangle and where small actions can have big consequences.

For generations, the dominant narrative of leadership has been that of a heroic leader, omnipotently making sense of what lies before them and forging a path for others to follow. But times are changing and this paradigm is not sufficient for the complexity of our schools. Of course, we still need positions of responsibility and accountability but success lies in collective leadership, not command and control as a default. Schools are not like machines that can be controlled. They are more like eco systems where life is interdependent.

So, sense making. Viviane Robinson reminds us that we should not design the future until we deeply understand the present. Robinson’s understanding is sense making; the extent to which we understand the reality of our school or a situation within it. This is no easy task, and research would suggest that adults have differing capabilities when it comes to appreciating the complex reality of school life based on their stage of ego development.

What is worth knowing about sense making?

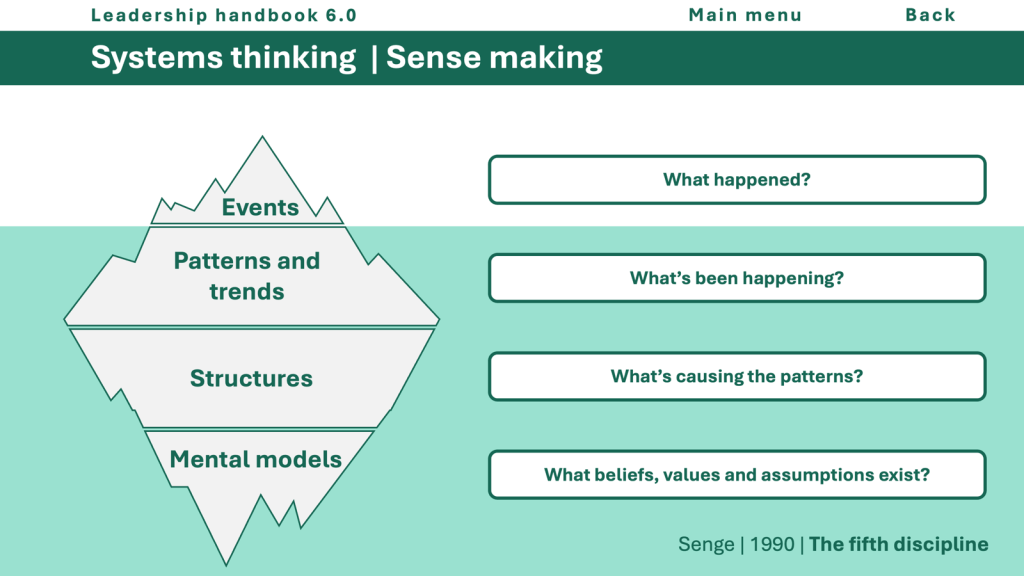

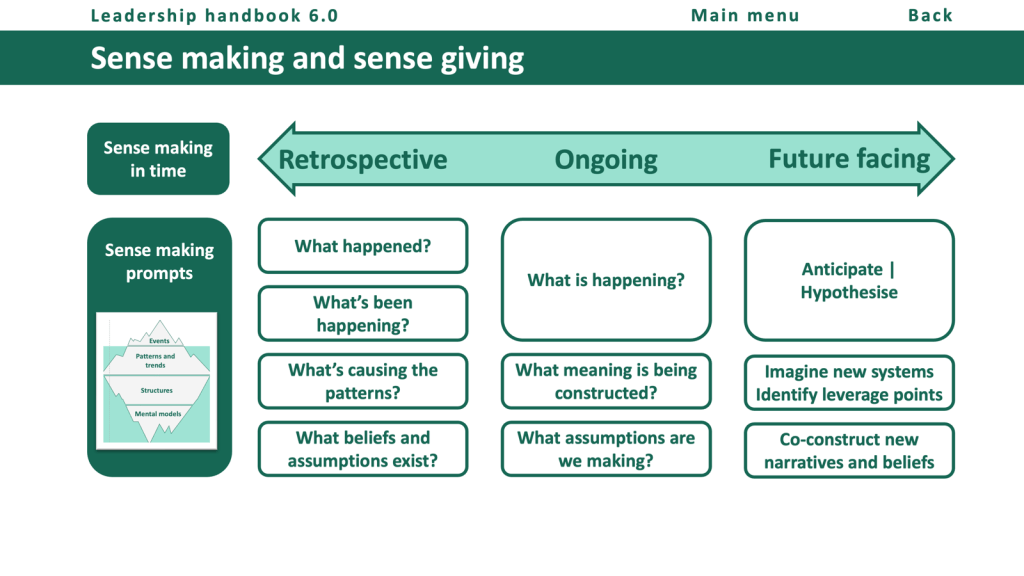

There is debate about when sense making happens, with some arguing that it is retrospective, after the dust has settled on our realisation that the map didn’t match the terrain; some arguing that it is ongoing, in the moment of realising that the map doesn’t map the terrain; and some arguing that it is future facing, where we anticipate that the map won’t match the terrain and plan accordingly. Whenever in time, useful prompts from Peter Senge’s work on systems thinking can help us make sense of a situation.

The deeper we go, the more likely it is that we’ll more fully understand a situation. These prompts are for retrospective decision making and are easily tweaked to help us make sense of a situation as it is unfolding or to anticipate a situation before it has happened:

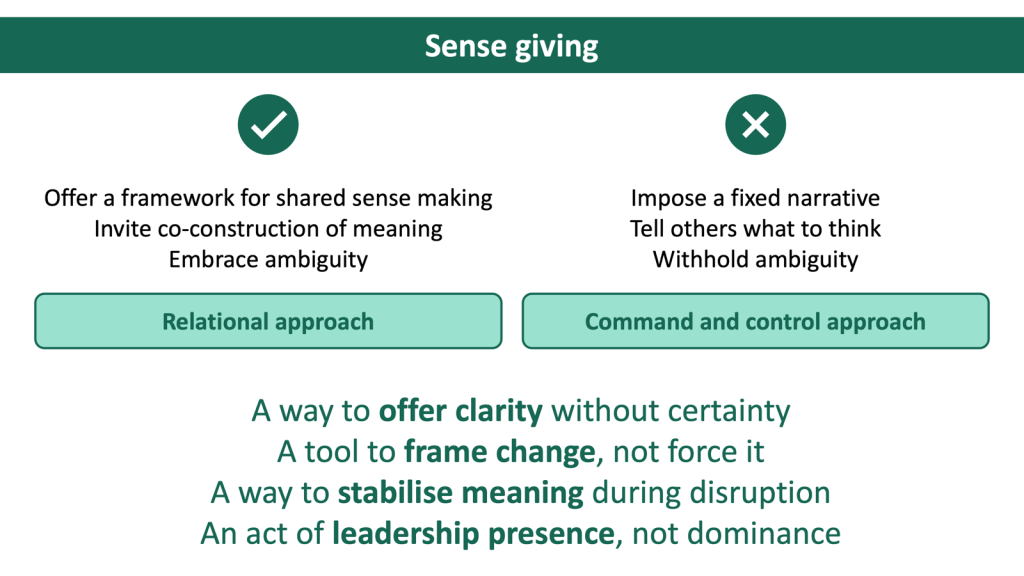

Can a group always make sense of a situation or do they need guiding? This is where sense giving comes in. Sense giving is supporting a group to make sense of a situation. Retrospectively, we might frame the past to help others to interpret events in helpful ways. In the moment, we might navigate the present, sharing information in real time and offering interpretations of it as we go. Future facing, we might inspire the future through how we talk about upcoming challenges and opportunities. All of which can nudge the group into aligned ways of thinking but this sense giving can look different under a command and control approach compared to a more relational approach.

When we approach sense giving (whether retrospectively, ongoing or future facing) with a more relational approach, we can offer clarity without certainty; we can provide a tool to frame change, not force it, we present a way of stabilising meaning during disruption and ultimately provide leadership presence instead of dominance.

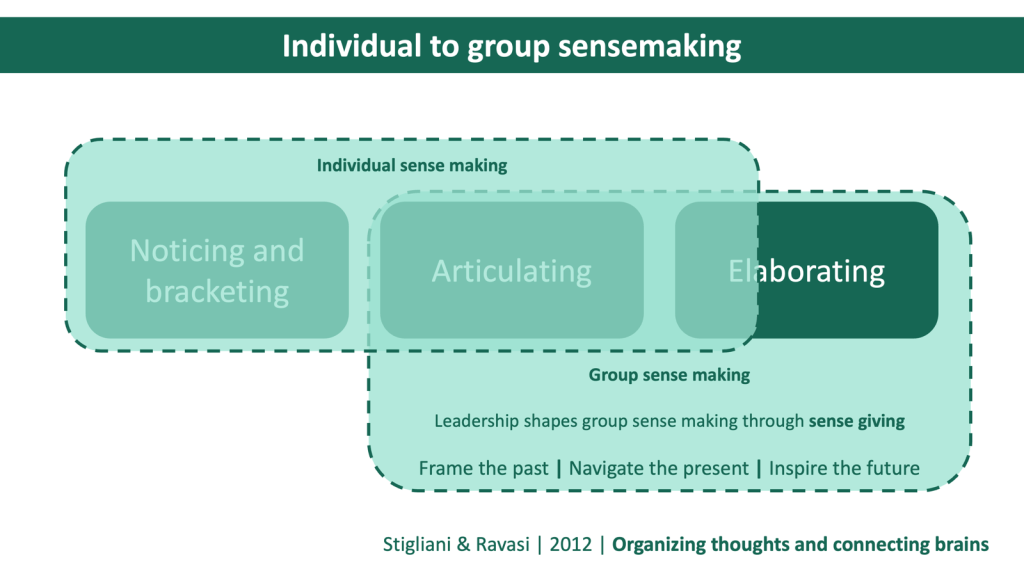

An important consideration is who does the sense making. In a hero paradigm of leadership, it’s a single leader that does the sense making but that’s not what we want. Group sense making is far more likely to yield the diversity of thought and consideration of the variety of factors that need interpreting. The paradox though is that individual sense making might well be the necessary prerequisite to group sense making:

In this model, group sense making requires individuals to notice that the map and terrain do not match; moments where we think: ‘That’s unusual’. And it requires individuals to bracket what they have noticed; deciding what’s worth paying attention to in the fog of complexity. Articulating is where individual sensemaking starts to become social. It’s the moment someone says: ‘I’ve noticed something…’ or ‘This is bothering me, and I can’t quite say why.’ That act of putting words to an internal signal is the first step in making shared meaning possible. This is itself sense giving; the team relies on model articulation because if no one says it, we can’t make sense of it together. Elaborating is where sense making becomes shared. When someone articulates something important, the next leadership opportunity is to host the elaboration; the space where that idea can grow, be tested, be made sense of together. This is where culture shifts. This is where alignment forms. From these interactions, direction, alignment and commitment emerge, not because one leader has provided them but because they have emerged through the interactions in the team.

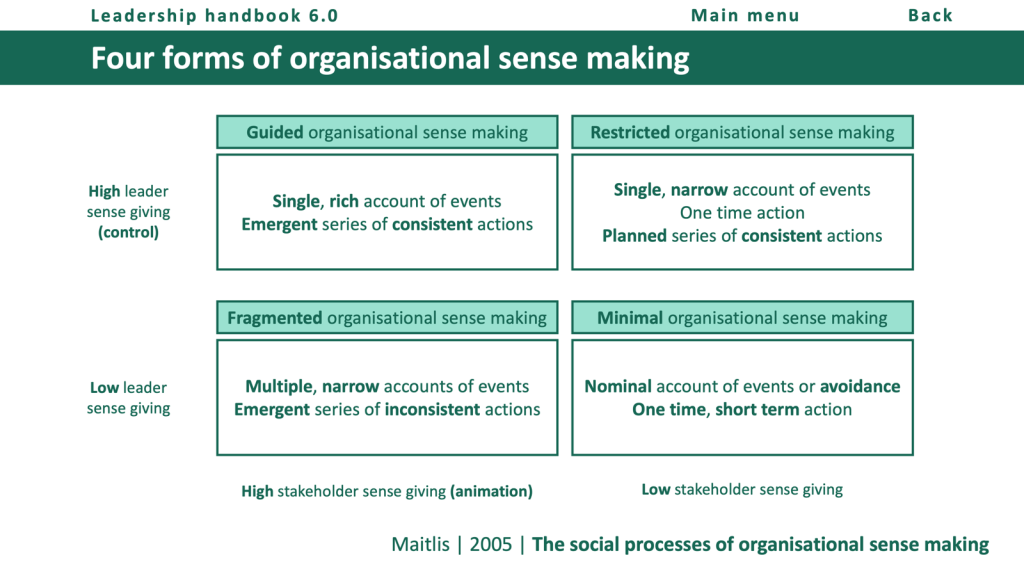

It is also important to consider the possible outcomes of group sense making because by noticing, bracketing, articulating and elaborating, it does not automatically result in accurate sense making. The balance of leaders and the wider team sense giving and the emergence of understanding through these interactions can result in quite different outcomes. At best, we might get a single, rich account of events and an emergent series of consistent actions; real shared understanding and aligned action. At worst, we might get a nominal account of events or even an avoidance of an issue, with a one off, short term action.

Sense making is therefore a vital part of school leadership. It’s where figure out, as much as is possible, the reality of school life and what we should do about it, which is far beyond the capability of one or even a small number leaders. The hero era of leadership theory is over and it is time to embrace relational approaches that far better enable us to appreciate the complexity of our school.